Uncomfortable Encounters with Truth

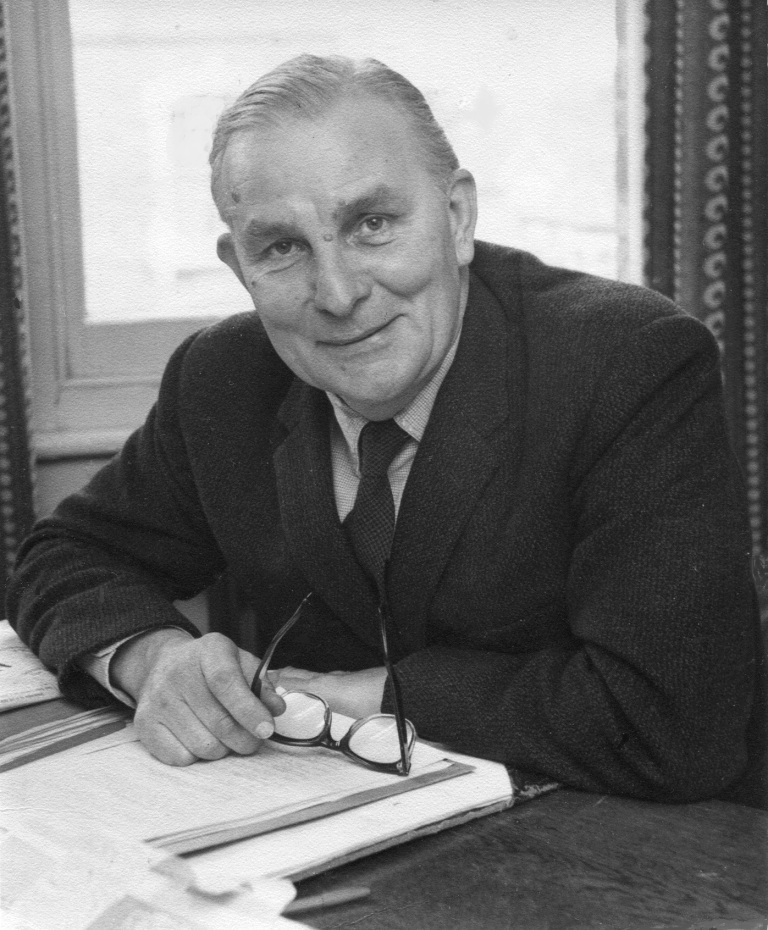

John Horner and the Communist Party, Uncomfortable Encounters with Truth (published by Routledge in 2024) is the biography of my father (1911 – 1997), a leading trade unionist and activist who became disillusioned with the Communist Party. It is for anyone concerned with the problem of political allegiance, personal morality and the associated states of denial that were to haunt my father in later life.

About the Book

The absence of primary sources makes books about twentieth century union leaders comparatively rare while university-educated, middle-class Communists are over-represented in the published lives of those who joined the Party in the 1930s. My father, John Horner’s highly readable but occasionally evasive, unpublished memoir of the first half of his life, along with the expansion of digitized press archives, are the vital sources that has allowed me redress the balance a little. At the same time, the records of a Quaker adult education centre in Walthamstow where my parents first met, along with childhood memory and family photos have enabled me to include an account of my mother’s maternalist feminism as an ‘activist in the shadows’, while also her husband’s confidante and keeper of his secrets.

My book tells the story of how and when a building labourer’s son from Walthamstow had already become a communist when aged only twenty-seven he was elected to lead the tiny Fire Brigades Union with just three thousand members. Two months later began the Second World War and the FBU grew twenty-fold by Horner recruiting auxiliary firefighters into the FBU and successfully campaigning to improve his members’ pay and conditions. I reveal how Party control over the Fire Brigades Union and the unethical demands made upon him eventually triggered a nervous breakdown and his subsequent resignation from the Party. Whereas Horner’s memoir ends in 1945 my story continues up to 1956/7, a decade when he served on the Communist Party’s National Executive and that he could not bring himself to include in his memoir, later telling the labour historian, John Saville, that he found himself ‘wallowing in apologia’ when attempting to do so. He and my mother resigned from the Party in 1956.

I see the book as a contribution to the history of the Left and of the trade union movement, thoroughly researched yet written to be accessible to undergraduate students and to a wider readership interested in radical history and politics of early to mid twentieth century Britain. I hope also that it will provoke readers’ interest in the vexed problem of political allegiance, personal morality and associated states of denial about which my father talked to me shortly before he died, a conversation that decided me eventually to write this book.